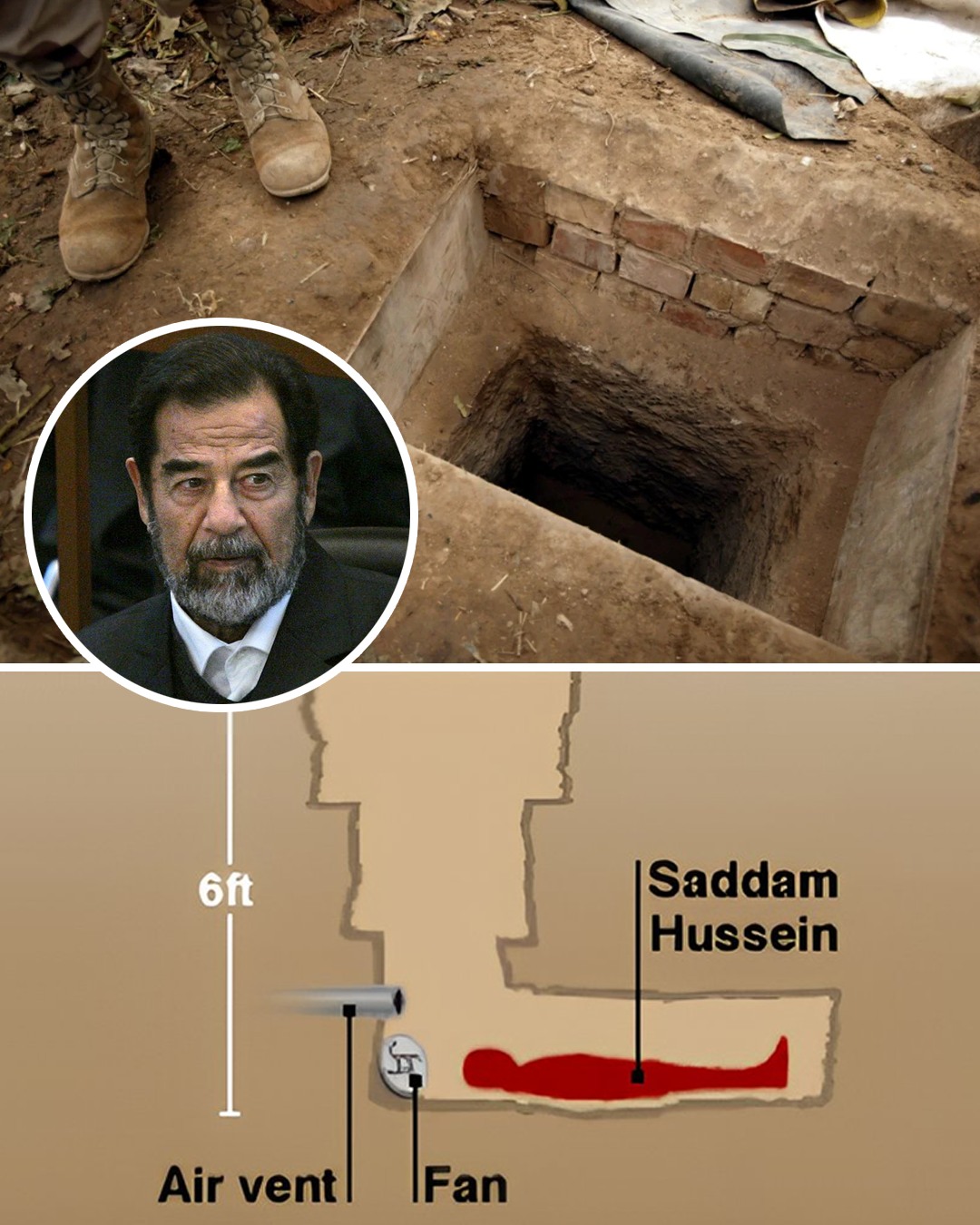

In December 2003, the world watched in astonishment as one of the most feared men in modern history was dragged from the shadows of obscurity into the harsh light of justice. Saddam Hussein, the former president of Iraq, a man who once ruled with an iron fist, was found not in a fortified palace or surrounded by legions of loyal guards, but hiding in a dirt-covered underground hole on the outskirts of his hometown, Tikrit. It was a moment that carried more symbolism than any battlefield victory. Here was a dictator who had commanded armies, built extravagant palaces of marble and gold, and silenced millions through fear, now crouched in a six-foot-deep “spider hole,” equipped with nothing more than a pistol, a small fan, and a crude ventilation system. The scene was both shocking and poetic—the mighty had indeed fallen.

The capture of Saddam Hussein on December 13, 2003, was not just another military operation; it was a turning point in the Iraq War and a historical spectacle that symbolized the collapse of tyranny. For months, U.S. forces had searched tirelessly, combing through villages, interrogating his former aides, and narrowing down his hiding spots. Saddam had evaded capture since April, when Baghdad fell to coalition forces, vanishing into the Iraqi countryside like a phantom. Rumors spread across the region: some claimed he had fled to Syria, others believed he was orchestrating resistance from the shadows, and many Iraqis whispered in fear that he was still untouchable. But on that December night, in a farmhouse near Ad-Dawr, the truth was revealed—Saddam Hussein was not the untouchable lion he had projected himself to be. He was a fugitive, dirty, unkempt, and cornered.

The hole itself became infamous. Barely large enough for a grown man to lie down in, the so-called spider hole was nothing more than a crude underground shelter covered with dirt and brush. Soldiers had to remove debris to access the hiding place, and when they lifted the cover, they found the man who once commanded Iraq with absolute authority. The image stunned the world: Saddam, with a long, scraggly beard, his hair wild and face weary, armed with only a pistol he never dared to fire. The contrast was staggering—once a leader whose speeches echoed across the Arab world, now reduced to silence, caught like a criminal trying to escape justice.

For Iraqis, the capture evoked a complex mixture of emotions. Some celebrated in the streets, waving flags, honking horns, and chanting in joy that the dictator who had terrorized them for decades was finally in chains. Others were skeptical, suspecting that the Americans had staged the capture, or fearful that Saddam’s loyalists would retaliate. Yet for the majority, the image of him pulled from the hole was seared into memory. It was proof that no ruler, no matter how brutal or seemingly untouchable, could escape accountability forever.

The significance of Saddam’s capture extended far beyond Iraq. Around the world, television networks replayed the footage of his medical examination, where U.S. soldiers checked him for lice and recorded his condition. The video was humiliating by design—it stripped him of the aura of invincibility and exposed him as a broken man. International leaders hailed the moment as a victory for justice. For U.S. President George W. Bush, it was a powerful vindication of the war in Iraq, a sign that progress was being made despite the mounting insurgency. The White House declared, “The former dictator of Iraq will face the justice he denied to millions.”

But beneath the celebrations lay sobering questions. Saddam’s fall did not bring immediate peace to Iraq. The insurgency raged on, fueled by sectarian divisions and anger at the U.S. occupation. In fact, many historians now argue that Saddam’s capture was both a symbolic victory and a grim reminder of the challenges that lay ahead. His regime had been toppled, but the deep fractures within Iraq—Sunni versus Shia, Arab versus Kurd—remained unresolved. The power vacuum left in his absence unleashed forces that would later contribute to years of bloodshed, civil war, and the rise of extremist groups.

Still, December 13, 2003, stands as a defining moment in modern history. It was a day when the myth of Saddam Hussein collapsed. For decades, he had carefully cultivated an image of strength and defiance, styling himself as a new Nebuchadnezzar, a modern Saladin who would resist Western domination. His portraits lined every street corner, his statues loomed over city squares, and his name was spoken with a mix of reverence and terror. Yet in that final act, hiding underground like a fugitive, Saddam revealed his humanity—flawed, frightened, and fragile.

The world took note of the irony. Here was a man who once ordered the use of chemical weapons against his own people, who built monuments to glorify himself, who launched wars that cost hundreds of thousands of lives, now dependent on a small air vent to breathe in a hole in the ground. History often has a cruel sense of justice, and Saddam’s capture epitomized that truth.

As the news spread, international headlines carried phrases like “The Tyrant in a Hole” and “Saddam’s Last Stand.” Political commentators compared the moment to the capture of Adolf Eichmann or the death of Adolf Hitler, symbolic ends to eras of fear. Yet unlike those figures, Saddam was alive, and his trial would soon become a stage for him to defend his legacy. When he later appeared before an Iraqi court, defiant and unrepentant, he tried to project the same arrogance that once terrified his nation. But the spell had been broken—the world had already seen him dragged from the dirt, powerless and humiliated.

Even today, more than two decades later, the image of Saddam Hussein being pulled from his spider hole remains one of the most enduring visuals of the Iraq War. It reminds us of the fragility of power, the inevitability of justice, and the fact that even the most imposing dictators can be reduced to hiding in the ground like fugitives. His capture was not the end of Iraq’s struggles, nor was it the conclusion of global debates over the war. But it was a rare, undeniable moment of clarity: the dictator was gone, and the world had witnessed his downfall in the starkest possible terms.

For those who lived through Saddam’s reign, the memory of his regime’s brutality—mass executions, disappearances, and the silencing of dissent—cannot be erased. Yet December 2003 offered a measure of closure. The tyrant who once seemed immortal was shown to be mortal after all, humbled by the march of history. The “Butcher of Baghdad” was no longer in command; he was a prisoner, awaiting judgment not only in a court of law but in the eyes of history itself.

The fall of Saddam Hussein, from his gilded palaces to a hidden hole in the ground, is a story that continues to resonate. It is a reminder that fear cannot sustain power forever, that even the most brutal regimes eventually crumble, and that justice, however delayed, can find its way through the cracks of tyranny. December 13, 2003, was not just the capture of a man—it was the capture of an era, the moment the world saw that dictators, no matter how powerful, are never truly invincible.